The latest DFNY focus features Japanese director Yukinori Makabe (真壁 幸紀), who was born in Tokyo prefecture in 1984.

He won the Grand-prix at the 2012 Louis Vuitton Journeys Awards with his short film “The Sun and The Moon”. The festival head juror was director Luca Guadagnino (Call Me by Your Name).

His first feature film “I Am a Monk” was released in 2015 and screened at many international film festivals.

In 2017, his short film”Home Away From Home” starred French actress Irène Jacob, winner of the 1991 Cannes Film Festival award for best actress.

“Love, Life and Goldfish” is his third feature film and first musical film.

Yukinori Makabe’s WEBSITE:

(日本語での表記は後に続きます)

DFNY: Love, Life and Goldfish was adapted from a manga by Noriko Otani, were there many changes made from the original story? Is music as important in the manga, or was that only in the film?

Yukinori Makabe: The musical element of the film is not in the original manga, it was established uniquely for the movie. When I read the manga for the first time, I was very impressed with the dynamic feeling of the pictures, it was as if I could hear music coming out of the pages. I made the film as a musical in order to convey that feeling to its maximum effect.

DFNY: Were your choices of including certain kanji intended as an homage to its manga origins?

YM: I was aware of the “speech balloons” used for writing dialogue in manga, but I also wanted to try and put the kanji on the screen as a way of having a much more vivid sensorial impression of the feelings that were being expressed.

DFNY: I was also curious if the Japanese title, すくってごらん (Sukutte Goran – “Please Try Scooping?”) is meant to be ambiguous, as both 掬う (to scoop) and 救う (to rescue) have the same pronunciation, すくう (sukuu). This was particularly noticeable in the lyric [すくいたくて], and I wondered if its potential double meaning was intentional. Additionally Kashiba’s desire to “rescue” Yoshino kept making me think of this possibility.

YM: That’s right, there are two meanings. Additionally it was important that the words rhymed with the feelings coming from Kashiba’s heart, as well as showing the uniqueness of the Japanese language and the word play that is possible. I’m curious to see how that aspect will be received by people who don’t understand Japanese at all.

DFNY: How was the development process? Were the songs written after the script was written, or before?

YM: First, a rough outline of the plot was written, including the parts where a song was to be inserted. Once that was completed, the music was written in parallel with the completion of the script.

DFNY: Were any songs left out of the final cut?

YM: No songs were ultimately cut out, but there were several that were rewritten so many times, that it feels like the total number of songs eventually written was huge.

DFNY: Do you have a background in music (playing an instrument, or singing) or making music videos? If so, how much of an impact did it have on your filmmaking choices?

YM: I was in a band when I was a student, so I can play the guitar. I’ve also directed several music videos. Additionally, a big part of my background is that the time of my youth overlapped with the beginnings of the Japanese rock festivals, when a lot of artists appeared and were able to sell millions of CDs. I think the fact that the Japanese music scene was so active when I was at such an impressionable age, and had so many opportunities to come into contact with music on a daily basis, is one of the factors which led to my eventually making a musical film such as this.

DFNY: Does the film have any other influences, such as Japanese folk tales, etc? I was particularly curious about the dance/crowd scenes and why the dancers/crowds had their faces concealed?

YM: The dancers and crowds are hiding their faces in a similar manner to how the “kuroko” (black-dressed stage assistants) of Kabuki do. For the film, it was necessary to show their physical movements, but I didn’t want their facial expressions to be seen. A face can convey a lot of information – for example, the audience might look at one of the performers and think they resemble someone, or have a large nose, etc, and so there is a high possibility that they might be distracted by something that has nothing to do with the film. I was trying to avoid that, and challenged myself to reveal the world of the film to the audience.

DFNY: How did you go about finding your cast? Were you looking for actors who could sing/play instruments, or the opposite, singers/musicians who could act?

YM: This film has many cast members who are very active on the stage. I like to see a wide variety of theatrical performances such as Kabuki and Takarazuka (an all-female musical theater troupe based in Takarazuka, Japan) and of course traditional plays and musicals, so I get a lot of information about actors from there. Kanako Momota is a singer, but I knew from her past appearances on the stage that she was very talented as an actress, so I offered her the role in the film.

DFNY: Did the different backgrounds (kabuki and pop music) of your two lead actors lead to any different approaches to their performances?

YM: Yes, there was contrast in my approach to the two of them. A lot of the attraction of Matsuya Onoe’s performance style is his spontaneity, so I didn’t give him a lot of detailed instructions and allowed him to perform freely. Even if there eventually needed to be some corrections, I would give him a rough idea of what I was looking for, but allowed him the flexibility to come up with some of his own performance ideas. And Kanako excels at intuitively grasping the type of performance I’m looking for, and is able to embody it with details like emphasizing the endings of certain words as well as her facial expressions.

DFNY: I have only seen two Japanese musicals (The Happiness of the Katakuris (カタクリ家の幸福) and Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る), and have only heard of maybe 20 or so others – are there many more musicals that aren’t well known, or does Japan not have as big a history with musicals as the United States? If so, do you think there is a reason? Also, some of my favorite Hollywood films are musicals (West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Camelot) – do you have any favorite musicals, whether Japanese or from another country (such as France’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg)? Besides the technical challenges, were there any box-office/audience concerns as to making a musical film?

DFNY: I have only seen two Japanese musicals (The Happiness of the Katakuris (カタクリ家の幸福) and Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る), and have only heard of maybe 20 or so others – are there many more musicals that aren’t well known, or does Japan not have as big a history with musicals as the United States? If so, do you think there is a reason? Also, some of my favorite Hollywood films are musicals (West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Camelot) – do you have any favorite musicals, whether Japanese or from another country (such as France’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg)? Besides the technical challenges, were there any box-office/audience concerns as to making a musical film?

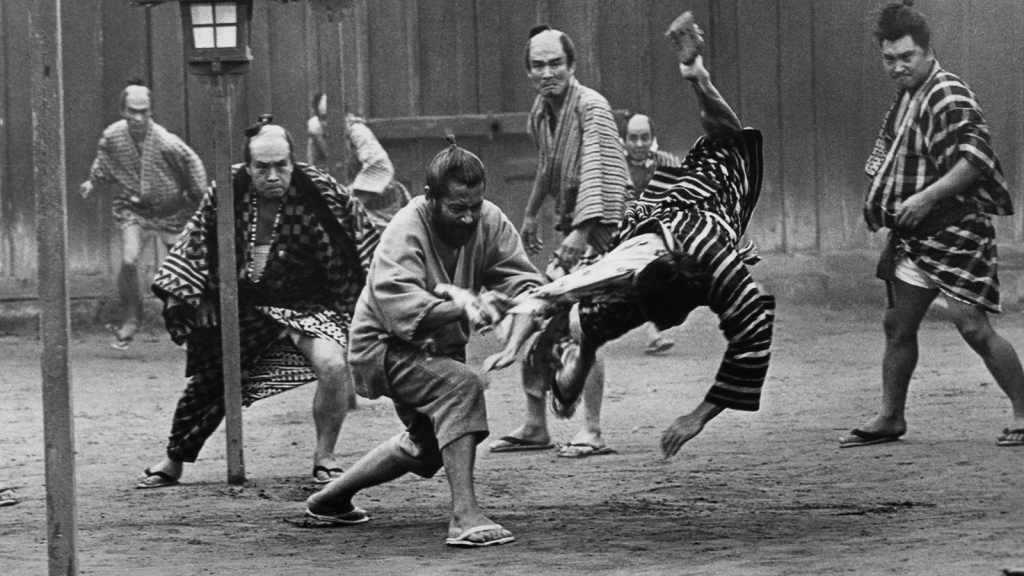

YM: The fact that there haven’t been any musical masterpieces in recent Japanese movies was one of my motivations for making this movie. In the 1950s and 1960s, the so-called golden age of Japanese cinema, many musical films were made. There were films from the band Crazy Cats such as You Can Succeed, Too (1964) starring Frankie Sakai and Japan’s Irresponsible Era (1962) starring Hitoshi Ueki. Love, Life and Goldfish is most likely influenced by the comedy films of that era. I consciously made the film thinking of the tempo, freedom, and strangeness of directors like Kihachi Okamoto or Yuzo Kawashima who made Suzaki Paradise Red Light (1956) which you had mentioned as one of your favorite Japanese movies (in DFNY Japan’s “DFNY Five”). The difficulty of making musical films in Japan lies in the Japanese temperament – our personalities are basically more shy and withdrawn, so if you try and make a musical movie that matches the tone of ones from the United States or Europe, it wouldn’t be a good fit for us.

What was interesting to me in my research for this film was learning about the difference in religious beliefs between Japanese people and Americans. For example, there are many churches in America, and I think it is common to pray to God. Therefore, the act of spreading one’s arms and exulting up towards the heavens as seen in so many musicals might not seem so unusual there. But this pose is not seen in Japan. In fact, if anything, prayer in Buddhism is performed with the hands placed together with the head facing down. In this film, we have excluded the more exultant scenes and have tried to have the songs emerge more naturally. I wanted to make a new sort of musical that Japanese people wouldn’t be ashamed to see. I made this film while strongly keeping that thought in mind.

———————————————————————————————————————–

真壁幸紀。

1984年生まれ東京都出身。

2012年にLouis Vuittonの映画祭Journeys Awardsでショートフィルム『The Sun and The Moon』がグランプリを受賞。

審査員はルカ・グアダニーノ監督。

2015年、長編第一作目『ボクは坊さん。』は多くの海外映画祭で上映された。

2017年にはショートフィルム『Home Away From Home』に1991年カンヌ国際映画祭主演女優賞のフランス女優、イレーヌ・ジャコブを迎えて制作。

『すくってごらん』は長編第三作目、初めてのミュージカル映画となる。

DFNY: ”すくってごらん”は大谷紀子による漫画からの映画化ですが、原作から大きく変えた点は多々ありますか?漫画でも音楽は重要視されていますか?それとも、映画の中だけのことでしょうか?

Yukinori Makabe: 音楽要素に関する部分は、原作の漫画にはない、映画オリジナルの設定です。漫画を初めて読んだ時に、音楽が聞こえてくるような、画の躍動感がとても印象的でした。それを映画として最大限に伝える方法として、ミュージカルにしました。

DFNY: 漢字をスクリーン中に入れているのは、漫画へのオマージュですか?

YM: 漫画の「吹き出し」を意識した部分はあります。

ただもっと感覚的に、心の声の表現として、漢字を画面上に出すという表現にトライしてみたかったという想いです。

DFNY: 日本語のタイトルも気になりました。「すくう」という音から、救うと掬うと二重の意図があると思いますが、主人公の気持ちを反映したものでしょうか?

YM: そうです、二つの意味を持たせています。また香芝の心の声は韻を踏んでいたり、日本語の面白さ、言葉遊びは大切にしました。日本語が全くわからない、外国の方にどう観てもらえるのか、興味深いです。

DFNY: デベロップメントのプロセスですが、曲が先にできて脚本を書いたのか、それとも脚本が先に出来ましたか?

YM: まず曲が入る箇所を含めた、大まかな構成プロットを作りました。それが完成したら、シナリオ作りと同時並行で楽曲を制作しています。

DFNY: 最終的にカットされた曲はありますか?

YM: 最終的にカットした曲はありませんが、それぞれの楽曲が完成になるまで、何回も作り直しているので、作った曲の数は膨大です。

DFNY: 例えば、楽器演奏や歌など、音楽的なバックグラウンドや、ミュージックビデオを制作したなどの経験はありますか?

そういった経験が映画制作の中でのクリエイティブな選択を行う上で、どのような影響を与えましたか?

YM: 学生時代にバンドを組んでいたので、ギターは弾けます。またミュージックビデオの監督も数作やっています。

それも含めバックグラウンドとして大きいのは、自分の青春時代が、日本のロックフェスティバル創世記と重なり、多種多様なバンド・アーティストが出てきて、CDが何百万枚と売れる時代だったという事です。

多感な時期に、日本の音楽シーンが盛り上がって、日常的に音楽と触れる機会が多かったことは、今回のような音楽映画を生み出すことになった、一つの要因だと思います。

DFNY: 日本の民話など、何か影響を受けていますか? 特にダンスや群衆のシーンで、なぜダンサーや群衆が顔を隠しているのかが気になりました。

YM: ダンサーや群衆が顔を隠しているのは、歌舞伎の黒子の手法を採用しています。

映画として、彼らの肉体の動きは必要だったのですが、表情は見せたくありませんでした。

顔の表情というのは、とても情報量が多いので、例えば「誰かに似ている」とか、

「鼻が大きい」とか、観客が映画に関係ない情報を受け取る可能性が高いのです。

今回はそれを遮断して、世界観を作ることにチャレンジしました。

DFNY: キャストはどのように見つけましたか? 歌えて弾ける俳優を探したのか、もしくは逆で、演技が出来る歌手やミュージシャンを探しましたか?

YM: 今回のキャストは、舞台を中心に活動している人が多いです。

僕はストレートプレイやミュージカルはもちろん、歌舞伎や宝塚など、多種多様な舞台を見るのが好きなので、そこから俳優の情報を得ています。

百田夏菜子さんは歌手ですが、彼女は女優としての才能もとても高い事が、過去の出演作でわかっていたので、オファーしました。

DFNY: かたや歌舞伎で、もう一人はポップミュージックという違うバックグラウンドを持つ主演の二人は、演技の面で違ったアプローチは見られましたか?

YK: 二人へのアプローチは対照的です。尾上松也さんは、ご自身が持っている衝動的なお芝居が魅力なので、細かい指示はせず、まずは自由に演じてもらいます。

そこで、修正があっても、大まかな演出をつけて、自分の中から、演技プランを出してもらう作業をしました。

百田さんは、こちらの演出意図を的確に捉え、それを体現する事に長けているので、台詞の語尾や、表情など、細部にわたり演出を付けています。

DFNY: 日本のミュージカルは2つしか観たことがありません。(「カタクリ家の幸福」と「カルメン故郷に帰る」)日本のミュージカルでは他に20作程しか聞いたことがありませんが、もっとたくさん知られていないミュージカルがあるのでしょうか?

それとも、日本はアメリカほどミュージカルの歴史が無いのでしょうか?

もしそうであれば、何か理由があると思いますか?

筆者にはハリウッド映画でいくつか好きなミュージカルがあるのですが、(ウェストサイドストーリーや、屋根の上のバイオリン弾き、キャメロット)監督には、邦画でも洋画でも、好きなミュージカルはありますか?

ミュージカル映画を制作する上で、技術的な問題の他に、興行的な問題や観客への配慮などありましたか?

YM: まさしく近年の邦画で、ミュージカルの代表作がないという事が、今回のこの映画を作る動機になった部分があります。

1950年〜60年代、いわゆる日本映画黄金期と呼ばれる時代には、ミュージカル映画がたくさん作られていました。

フランキー堺さん主演の『君も出世ができる』や植木等さん主演の『ニッポン無責任時代』に代表されるクレイジーキャッツ映画など。

今回の『すくってごらん』はその時代の喜劇映画に多分の影響を受けています。

Toddさんも好きな映画に挙げていた『洲崎パラダイス赤信号』の川島雄三監督や岡本喜八監督の、テンポ・自由・奇妙さ。

そのあたりは、意識して制作しました。

日本でミュージカル映画がなかなか難しいのは、やはり日本人の気質にあります。

基本的にシャイでテンションは低いので、そこをアメリカやヨーロッパのテンションに合わせてミュージカル映画を作ろうとすると、どこかで無理が出ます。

また今回作るにあたり、研究して興味深かったのは、宗教観がとても大きいという事に気づきました。

アメリカでは教会が多くあり、神に祈る事が日常であると思います。

いわゆるミュージカルに代表される、「手を広げ、天を仰ぐ」という行為が、様になるのは、日常的に同じような形があるからです。

しかし、日本にはありません。

あるとしても仏教で、手を合わせ、下を向いて祈ります。

今回は、いわゆる「手を広げ、天を仰ぎ、歌う」というシーンは排除していますし、突如歌い出すという事への違和感をなるべく和らげるようなシーンの作り方をしています。

「日本人が見ても恥ずかしくない新しいミュージカル映画」にしたい。

その想いを強く持って、制作しました。

DFNY: I have only seen two Japanese musicals (The Happiness of the Katakuris (カタクリ家の幸福) and Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る), and have only heard of maybe 20 or so others – are there many more musicals that aren’t well known, or does Japan not have as big a history with musicals as the United States? If so, do you think there is a reason? Also, some of my favorite Hollywood films are musicals (West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Camelot) – do you have any favorite musicals, whether Japanese or from another country (such as France’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg)? Besides the technical challenges, were there any box-office/audience concerns as to making a musical film?

DFNY: I have only seen two Japanese musicals (The Happiness of the Katakuris (カタクリ家の幸福) and Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る), and have only heard of maybe 20 or so others – are there many more musicals that aren’t well known, or does Japan not have as big a history with musicals as the United States? If so, do you think there is a reason? Also, some of my favorite Hollywood films are musicals (West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Camelot) – do you have any favorite musicals, whether Japanese or from another country (such as France’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg)? Besides the technical challenges, were there any box-office/audience concerns as to making a musical film?